Data released this month by Governor Charlie Baker’s administration reveals the coronavirus pandemic disproportionately impacts people of color in the state.

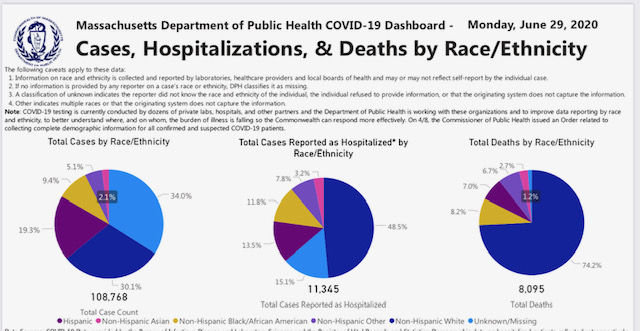

Hispanic, Latinos account for 30-percent of the cases and 16% percent of the hospitalizations – even though they make up only 12-percent of Massachusetts’ overall population.

The state Department of Health also notes that the Black community account for 7-percent of the state’s population but 14-percent of COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations.

The rate Hispanic, Latino, and Black cases are more than three times that of White residents. By contrast, CommonWealth (CW) reports Whites account for 71.5 percent of the population but only 45-percent of cases and 57-percent of hospitalizations. Asians account for 7-percent of the population, but only 3-percent of cases and 4-percent of hospitalization.

State Department of Public Health Commissioner Monica Bharel said the findings are the latest indicator that “change is necessary” to address racial inequities in public health, reported WCVB.

Similarly, the Connecticut Health Foundation advised that as this disease unfolds, it is important to recognize the roots of these disparities including differences in access to health care, unequal treatment within the health care system, unequal access to resources such as stable housing and healthy food, and personal experiences of discrimination and racism that have lasting physical and mental health consequences.

SUGGESTION: COVID-19 in context: Why we need to understand the roots of health disparities

Some key facts:

- Having a regular source of care is a key factor in staying healthy; now, it also means having a place to call if you feel sick and wonder if you need to be tested for COVID-19. Yet in 2018, 33% of Hispanic residents and 23% of black residents did not have a personal doctor (by contrast, only 11% of white residents reported not having a personal doctor).

- Research has also found that black and Hispanic patients are at risk of receiving less aggressive treatment than white patients. For example, studies found that Hispanic patients were half as likely to be given pain medication when they went to the emergency room with a broken bone, and black children and teens with appendicitis were significantly less likely to be given opioids to treat pain. Among patients with heart issues, black patients were significantly less likely than white patients to receive interventions that could promote long-term survival.

- Research has also linked experiencing racism and discrimination with a wide range of negative physical and mental health consequences including depression, anxiety, hypertension, breast cancer, and giving birth preterm or having a low-birthweight baby. One way discrimination could lead to poorer health is through repeated activation of the body’s stress response system, which can have negative long-term physical and psychological effects.

The Massachusetts’ data also shows that Hispanics, Latinos in Massachusetts account for 7-percent of overall deaths from COVID-19.

Whites account for 73.5-percent of deaths, Blacks 8-percent, and Asians 3-percent.

But according to CW, the Baker advisory group said a better way of looking at fatalities was to use age-adjusted data, “given differences in the underlying age distribution of the MA population by race, and differences in COVID-19 death trends by age.”

Using that approach, the age-adjusted death rate for Blacks was highest at 161.4 per 100,000 Black residents. For Hispanics, Latinos it was 132.8 per 100,000. Whites and Asians were much lower, at 75.3 per 100,000 and 65.6 per 100,000.

In its recommendations, the COVID-19 Health Equity Advisory Group blamed the disparate impact of COVID-19 on “racism, xenophobia, and lack of economic opportunity.”