Jennifer De Leon was preparing for her creative writing class in 2010, rummaging through her bag, when a student approached her and asked about the teacher.

“Hey, do you know when the instructor is gonna get here?” the student said to her.

“I’m sitting right here,” she responded.

De Leon, who recalled the encounter in an interview, is very familiar with being made to feel like an imposter in a classroom even though she is an accomplished editor, speaker, professor, mother and Juniper prize-winning author.

She said she spent the rest of the class wondering if she was even qualified for the job.

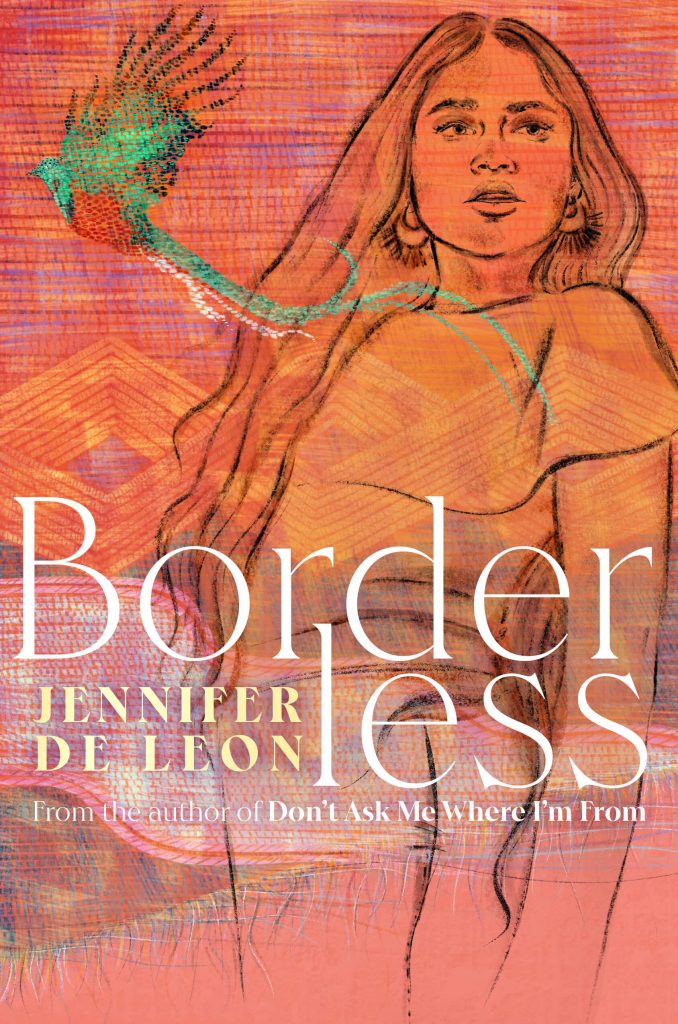

De Leon released her latest book Borderless in April and has made it her mission to showcase the multidimensional reality of Latin cultures and being a Latina in white spaces. She’s written multiple books and essays that amplify complex Latino voices and is teaching a new generation of ‘unknown storytellers’ how to write their own stories.

“I feel strongly about writing (and) bringing (people who) traditionally have been in the margins to the center,” she said.

De Leon, the daughter of Guatemalan immigrants, had never read a book by a Latina author until she was 19 years old and in her freshman year of college.

That’s when she read The House on Mango Street by Mexican-American author, Sandra Cisneros. De Leon described the book as “crisp” and “alive,” with sprinkles of Spanish dialogue that echoed the voices of her family members.

Until then, she did not know authors were “allowed” to break the stylistic statute set by the white and male authors, like Ernest Hemingway or Raymond Carver, that she was typically assigned. De Leon said Cisneros’ dialogue spoke to her on so many levels that, “I honestly thought the professor made a mistake.”

To relay an authentic story arc in her recently published book, De Leon traveled to the US-Mexico border at McAllen, Texas, to document first-hand accounts of people who risked their lives to come to the United States.

When De Leon was two years old, her parents moved 1,182 miles south of Boston to the suburbs of Birmingham, Alabama, so she and her sister would have the “best education.” But her life started to become divided.

She said she felt stereotyped in high school and was forced to assimilate in her largely white school. In one troubling incident, De Leon recalled one of her teachers telling her to hurry up or she would miss the “Metco bus.” Metco is a desegregation program that transports students of color to schools in the suburbs. But the teacher had no idea that De Leon lived near the school and could walk home.

De Leon, the only person of color in her class, said she did not have the language to name what she was experiencing.

But she said she felt like she did not belong there.

Now, through her writing and other work, she’s helping people in her community embrace their cultural differences and promote diversity, equity and inclusion through storytelling. Her organization, Story Bridge, also explores stories from participants’ own lives.

At a book reading in Porter Square this past February, De Leon and Patricia Park—author of “Imposter Syndrome and Other Confessions of Alejandra Kim”—spoke candidly about how growing up in white spaces as children of immigrants is a dual battle.

Park explained that beyond her own expertise as an Argentinian-Asian American, she’s still learning about who confronts imposter syndrome and how it manifests itself in society.

De Leon said she will keep pressing her issues to students and others in her workshop.

In her classroom story about feeling like an imposter, De Leon said she spent the entirety of the creative writing class battling her inner voice that doubted if she was qualified for the job.

“I am the professor,’’ De Leon said, “you shouldn’t doubt that.”

She recalled the words of her mother that gave her some peace.

Do not be an imposter, her mother had told her, take up space.

This report was published in collaboration with the Boston University School of Communications School of Journalism. The journalism student is a member of a Reporting in Depth class taught by former Boston Globe reporter Meghan Irons.